In port cities with a heavy industrial past, such as Montreal or Barcelona, the transition to the new economy at the turn of the millennium precipitated a host of factories, warehouses and spaces into total disuse and it became necessary to give a new vocation to these places, which were often close to the port. The technical term used for this in urban planning is requalification.

Barcelona tackled the problem brilliantly in the Poblenou district, where such a transformation has been taking place for twenty years. A transformation so skillfully orchestrated that it has become an urban laboratory grasping attention from all around Europe. Here are some lessons from the 22@ project.

Lesson #1 : take your time

What is going on in Poblenou could be transposed in whole or in part to the former refineries in Montreal East or to the future redevelopment of the former Blue Bonnets site west of Décarie. And some of the ideas being developed here could possibly have greatly improved the development of Griffintown if we had just taken a little bit more time. As urban strategist François Duchastel, partner at Voodoo Associates, explains in the interview he gave us in Barcelona in July 2022, the Adjunament de Barcelona was not afraid to consult with communities and experiment from the get go in 2001. It didn’t all happen all at once.

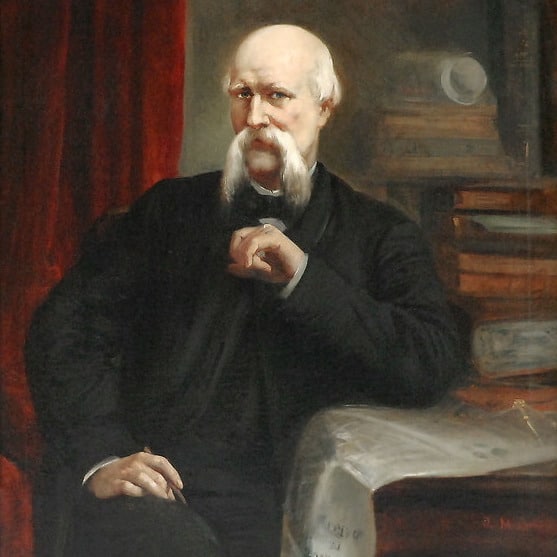

Barcelona’s city grid has more than 550 blocks of 113 square meters as designed by civil engineer Ildefons Cerdà in 1856.

Superilla = super block

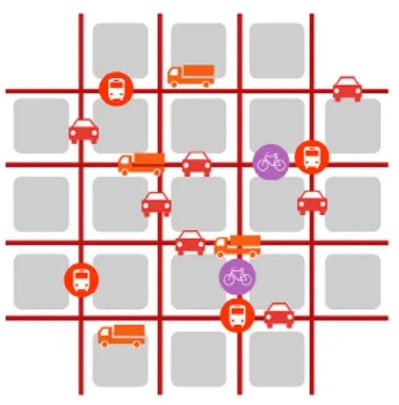

One of the great innovations of the 22@ experience is that a few “super blocks” – the superillas – were created to form groups of three blocks by three blocks considered as entities in their own right, sort of safe and peaceful enclaves in he city.

Lesson #2: don’t focus so much on the automobile

What is particularly interesting about the 22@ project in Poblenou is that the City of Barcelona was strongly inspired by it and extended it to several other districts of the Catalan metropolis. Like the superillas deployed in Poblenou, Sant Antoni and Hostafranc, Barcelona now wants to free up spaces for citizens and pedestrians across the city. Other large areas will be developed by the end of 2023. This is a clear attempt to promote social interaction nd environmental protection and reduce the importance traditionnally given to motor vehicles. Especially when it comes to traffic inside the superillas. In the new plans, we are switching from all-out motorized traffic to shared mode and by limiting car access almost exclusively to residents, at very low speed, inside the superillas.

BEFORE

SUPERILLA

Credit: City of Barcelona

Lesson #3 : consult and mobilize communities

From a public participation point of view, Barcelona’s know-how is recognized worldwide. In the opinion of urban strategist François Duchastel, the contribution of communities is indeed crucial to the productive development of requalification projects.

“I think we must find strategies for people to participate in a concrete way without just being in opposition, but to really participate. And that’s where co-design projects, co-participation, on specific elements where people can really have an impact on their living environment, and then be able to say, yes, we influenced that. Barcelona did it, among other things, by district of the city. They identified about twenty projects, allocated budgets and then opened on a digital platform, which people can vote to decide. Is it a priority here to make land that would become a planted park? Or do we prefer to make a space elsewhere that would be a space for children’s play? Or are we going to remove a traffic lane instead? People were able to speak out. Here it would cost 600,000 euros, here it would cost 1.2 million, then decide how to allocate the budget. »

The founding father of modern-day urban planning

Urban planning was invented in Barcelona. Literally. Its creator is civil engineer Ildelfons Cerdà, who was entrusted with the planning of the Exaimple, the extension of Barcelona outside the fortified walls starting in 1859. We therefore owe him the first urban development plan, the Cerdà Plan. It is this checkerboard-shape urban grid so characteristic of Barcelona, which is unique in that the angles of its blocks are cut at 45 degrees to allow for better visibility at intersections. He also wrote Teoría general de la urbanización which is still taught in major schools.