Another Miami

As Miami’s legendary spring break approaches, we present two inspiring public participation initiatives in Magic City. We tend to forget: Miami is not just about tourism, beaches and parties. There are also thousands of ordinary people living in working-class neighborhoods. Two public participation (P2) initiatives particularly impressed us: Little Havana and Wynwood Norte.

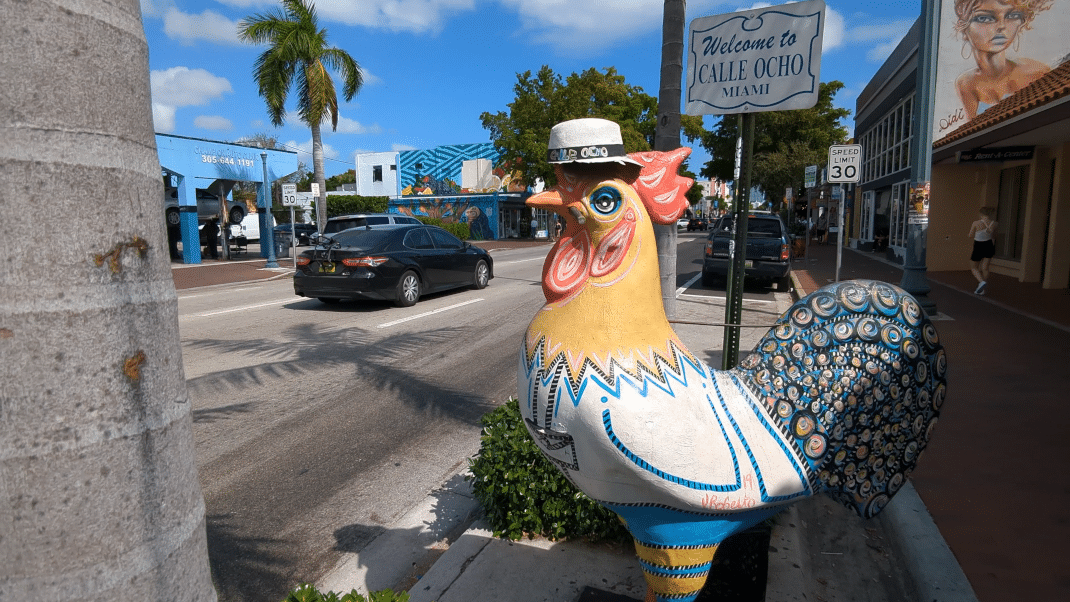

Little Havana

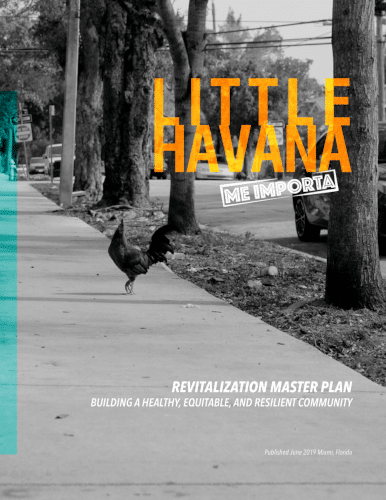

Juan Mullerat is the founding principal of Plusurbia Design. He gave us a tour of Little Havana and told us about the ultra-innovative approach that his firm put forward to mobilize the local population of “Little Havana”, a neighborhood where he actually lives. All in all, nearly 2,000 people got involved in the various stages of this vast public participation (P2) program with the aim of redefining their residential neighborhood. An initiative that Juan and his firm will have piloted for nearly four years in collaboration with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Their joint 170-page report, Little Havana Me Importa (I care about Little Havana) was released in June 2019 and the proposed changes have started to slowly get implemented.

The Little Havana Revitalization Plan is described as a roadmap for the future health and vitality of the neighborhood, developed in collaboration with residents and stakeholders.

At the unveiling of the report, Miami Mayor Francis Suarez had this to say about the project: “I am beyond blown away. There has never been a more comprehensive study done in any neighborhood in the city of Miami and to me, that master plan is not just a document; we need all of you to make this a reality”.

CONTINENTAL CROSSROADS

Miami’s population was 439,890 people in 2021 and 6.1 million people including Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach, which places the urban area eighth in the United States. Interesting fact: 72.5% of Miamians say they are of Hispanic or Latin American origin.

Wynwood Norte

Following the Little Havana project, Plusurbia undertook another requalification process not far from there, in the Wynwood Norte district. This time the mandate came directly from a real estate developer that was really visionary to say the least. He was convinced that the Little Havana approach was the right way to go.

With other specialists and consultants, Plusurbia was given the task to revitalize the area and to mobilize this typically Puerto Rican neighborhood, in which the developer held interests. Juan Mullerat told us that the very first stage of the project, surprisingly enough, was very simple: they started by creating an association of residents and stakeholders. There was none before Juan and his team decided to bring together key players.

The public participation program then mobilized the members of this new association and the population of Puerto Rican origin. Starting from there, it was possible to record their “ideas-needs-desires-vision” and develop a common vision for the sector.

It must be said that the City of Miami believed in the project and embarked on the adventure just as much as the citizens. Wynwood Norte’s first Master Plan was therefore officially adopted by City Council last fall.

During our interview in Miami, Juan Mullerat talked about the spark that is needed for these kinds of initiatives and talked a lot about the charrette procedure for conducting brainstorming workshops with large groups of people, an approach that COLŌKIA also likes to use a lot (our record: a charrette of more than 150 people in Québec City).

The charrette procedure

One could say that the Charette procedure is a way to instill “fair and equitable creativity” by allowing large groups of participants to brainstorm on several topics at once. The technique involves randomly dividing participants into smaller groups, with each person speaking in turn, until everyone at the table has had a chance to fully contribute.

The concept was invented by architecture students in the early 19th century. They literally used carts to propel their sketches across the room to get final approvals. Similarly, in a charrette, the ideas generated by one table are transferred to the next group, to be developed and/or refined and ultimately prioritized.

Property developers or city builders?

During our interview, Juan Mullerat was amused by the expression “real estate promoter” (promoteurs immobiliers) that we use in Quebec. In fact, it was the term promoter that made him smile because he feels that developers, in English -or promoters- are in fact “city builders” to use his own words and that we owe them a lot, even if we like to accuse them of all the evils related to the housing crisis. In fact, the real problem, according to him, is “unmanaged change”, i.e. when the culture of a neighborhood and the contribution of its residents are not taken into account at all and when development is done in an uncoordinated manner.

He also spoke of the essential role of cities in the public participation process – in complete equality and not as leaders – and of the great need for public participation professionals to dream big and have ambition for the communities they serve and represent.